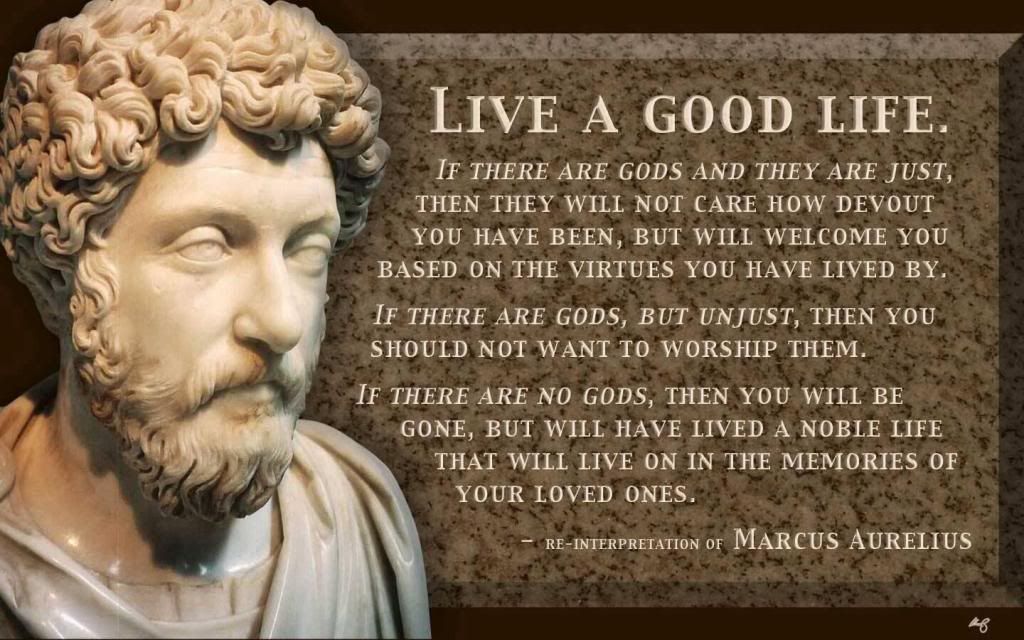

Marcus Aurelius was the last of Rome's "Five Good Emperors." As a Stoic philosopher, he lived a simple life with (for an Emperor) few pleasures. His creed as shown above dictated a life of virtue, but not devotion to the gods. He was what we would call today a "salvation by works" kind of guy. He reasoned that if he lived a good enough life, then just gods would allow him to be welcomed into their company. If they were unjust, then being admitted to their company was not desirable. If no gods existed, then his noble life would at least inspire his loved ones who lived on.

The man was a fabulous and just emperor all the way to the end of his reign. His highest pleasure seemed to be ruling wisely and justly. Examining his performance, and those of his four predecessors, could almost convince one of the virtue of the central state left in the hands of virtuous rulers.

Aurelius though, had a fatal conceit. Fatal to the Roman Empire and the ideas of justice he cherished. He did not understand his own nature. Men are not good, except when compared to one another. None can be trusted with great power over others indefinitely. It goes to their heads, in most cases in ways that are obvious, and in other cases ways that are more subtle but just as vainglorious and destructive.

In the Christian view, the religion that was sweeping through the empire during the reign of Aurelius, devotion to God was not just another way to earn points to get accepted into God's company. Rather it was a heartfelt response to the knowledge that though we are not virtuous, God Himself provided a way into His company which we could not otherwise earn. By the tenants of this faith

none are righteous,

none are worthy, on the basis of our own virtue, to sit in the presence of God. Indeed, in the course of time the great thinkers and theologians of this faith concluded that none but God alone are worthy, on the basis of their own virtue, to sit on a throne over the rest of mankind. The rulers need restraints on their behavior as much as the ruled, perhaps more so. The law of heaven, whatever it may be, was above both and if the laws of man did not reflect its heavenly ideal then it was the rulers who made them which were unjust, not the citizens who might demand their abolishment.

None of the previous "Good Emperors" had a son of their own blood. Each of them adopted as sons someone who was responsible and as virtuous as humans can be. Though sitting on the throne would in time reveal the corruption present in any man, they wisely picked men who had already shown an aversion and resistance to corruption and in whom the habits of moral living were deeply ingrained. The mortality of man would take them from the earth before the corruption of the throne had greatly marred their character.

Not Aurelius. He did not choose this path. He had a son of his own blood, Commodus. He was determined to make his own son the next Emperor rather than to continue the tradition of adopting someone who had shown themselves worthy, at least for a time, of holding such power. Commodus loved corruption as much as his father loved justice. Commodus had a close-up view of his father's sanctimonious living and self-righteous attitude. Rather than being attracted to it, as Aurelius assumed his loved ones would be, he was off-put by it. He went the other way with reckless abandon. He denied himself no pleasure, and he took no delight in justice. It was a pagan version of the "preacher's kid" syndrome, which is to say, a consequence of an excessive pretense of self-righteousness in parents, whatever one's faith.

The rule of Commodus was a disaster. That was the beginning of the end for mighty Rome. The willful decision of Marcus Aurelius to make Commodus his successor rather than adopt someone who had demonstrated a life of virtue was an outcome of his fatal conceit which dominoed into the destruction of the Roman Empire. Despite his philosophy and life of good works, with such a great blame laid at his feet one can imagine that even were the Roman gods just, they might justly ban him from their company.